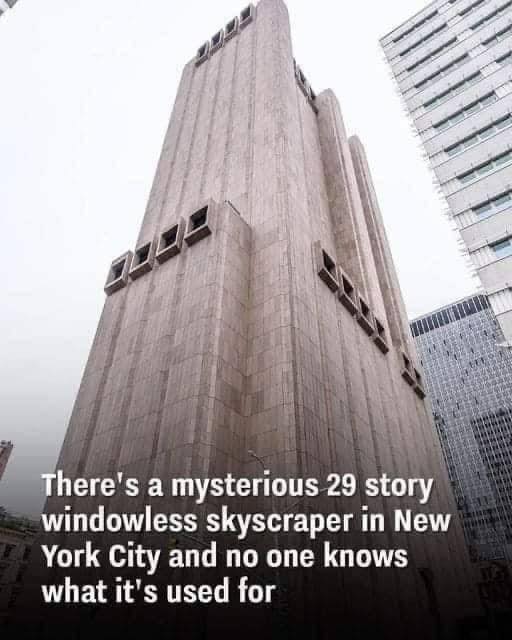

In Lower Manhattan, a remarkable skyscraper stands out among the bustling streets and towering buildings. Known as Titanpointe, the 29-story structure at 33 Thomas Street has intrigued New Yorkers for decades. Its most striking feature? The complete absence of windows, which only adds to the air of mystery surrounding it.

Built in 1974, the building was designed to withstand catastrophic events, including atomic blasts. Its primary purpose was to house critical telecommunications equipment. Designed by the architectural firm John Carl Warnecke & Associates, the structure was envisioned as a fortified communication hub, resilient against potential nuclear threats during a tense period in global history.

Standing at 550 feet tall, this imposing concrete and granite tower is a stark contrast to its neighbors in the New York City skyline. Unlike the surrounding residential and office buildings, 33 Thomas Street remains unlit and unwelcoming, both day and night. By day, it casts an imposing shadow, while by night, its unadorned exterior and humming vents create an eerie atmosphere. The absence of windows only amplifies its enigmatic presence, making it an enduring source of speculation and fascination.

Dubbed the “Long Lines Building,” 33 Thomas Street has long captured the imagination of locals and visitors alike. While its purpose as a telecommunications center has been widely accepted, recent revelations have painted a far more complex and secretive picture. The building’s true function may extend beyond mundane telecommunications, hinting at a much deeper involvement in government surveillance.

Documents released by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden, combined with architectural plans and testimony from former AT&T employees, suggest that 33 Thomas Street is more than a simple communications hub. These sources indicate that the building has operated as a surveillance facility for the National Security Agency (NSA), under the code name Titanpointe.

Far from being mere speculation, evidence points to the presence of an international gateway switch inside the building. This switch reportedly handles phone calls between the United States and various countries, providing the NSA with a unique opportunity to intercept communications. Allegedly, the NSA has used this facility to monitor calls involving international organizations such as the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank, as well as communications from allied nations. The scope of this surveillance has raised significant concerns about the balance between national security and privacy.

The collaboration between AT&T and the NSA adds another layer of complexity to the story. While the telecommunications giant’s partnership with the government is well-documented, the precise extent of its involvement at 33 Thomas Street remains unclear. Snowden’s disclosures shed light on the use of NSA equipment within AT&T’s network in New York City, illustrating how the agency has accessed data from the company’s infrastructure. Yet, definitive proof of the NSA’s direct activities within the building is still elusive.

This revelation has sparked broader discussions about the limits of surveillance in today’s interconnected world. Elizabeth Goitein, co-director of the liberty and national security program at the Brennan Center for Justice, underscores this concern. “This is yet more proof that our communications service providers have become, whether willingly or unwillingly, an arm of the surveillance state,” she says. The close relationship between the NSA and domestic communication systems challenges the assumption that surveillance primarily targets non-American entities.

AT&T’s role in this partnership has drawn scrutiny, particularly regarding its willingness to collaborate with the NSA. Reports from The New York Times and ProPublica in 2015 highlighted the company’s longstanding cooperation with the agency, describing AT&T as exceptionally accommodating. However, even with these revelations, there is no concrete evidence directly linking the NSA’s surveillance operations to AT&T’s facilities at 33 Thomas Street. While AT&T occupies most of the building’s space, Verizon also maintains a smaller presence within the structure.

The potential use of 33 Thomas Street as a surveillance hub raises critical ethical and legal questions. In an era defined by digital connectivity, the building serves as a symbol of the delicate balance between privacy and security. It also highlights the challenges of ensuring proper oversight in the face of rapidly advancing technology and evolving government surveillance capabilities.

The existence of a facility like Titanpointe forces us to confront uncomfortable realities about the extent to which our communications are monitored. While government surveillance is often justified as a means of protecting national security, it also poses significant risks to individual privacy. The lack of transparency surrounding such operations complicates efforts to establish meaningful accountability.

Ultimately, 33 Thomas Street represents more than just a distinctive architectural feature in New York City’s skyline. It embodies a broader debate about the role of surveillance in modern society. Its shadowy history, steeped in both telecommunications and government monitoring, serves as a powerful reminder of the ongoing tension between privacy and security. As technology continues to evolve, so too will the questions surrounding the limits of surveillance and the measures needed to protect individual freedoms.

While the full extent of 33 Thomas Street’s involvement in government activities may never be known, its story underscores the complexity of living in a digital age where secrets are harder to keep, yet privacy feels increasingly elusive.