The inevitability of aging is a reality that every one of us must face. It’s an inescapable part of life, a natural progression that reminds us of the passage of time. However, amidst the changes that come with growing older, there are many aspects of life that remain constant—things that we may take for granted, yet hold immense beauty when we stop to truly appreciate them. Have you ever paused for a moment to fully immerse yourself in the sounds of nature? The gentle chirping of crickets on a warm summer night, the melodious songs of birds greeting the morning sun, or the rhythmic croaking of frogs as they communicate across a pond? These sounds form a natural symphony that we often dismiss as mere background noise. But have you ever considered listening to something even more unusual—something that most people wouldn’t even think to listen to? Have you ever thought about what a tree trunk might sound like?

Yes, you read that correctly. A tree trunk. While it may seem like an odd notion at first, there’s a fascinating concept behind it. When we talk about “listening” to a tree trunk, we’re not referring to the sounds of the wind rustling through its leaves or the creaking of its branches as they sway in the breeze. Instead, we’re referring to the rings inside the tree—the intricate patterns that form over the years, each one telling a story of growth, survival, and the environmental conditions it endured. These rings serve as a natural archive of the tree’s life, preserving valuable data that reveals its age, the climate it experienced, and even certain environmental factors it had to overcome. But beyond their scientific significance, these rings have an unexpected capability—they can produce music, much like a vinyl record.

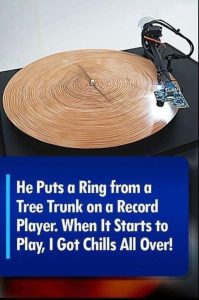

As unbelievable as it may sound, an artist named Bartholomäus Traubeck has turned this concept into a reality. Through a groundbreaking fusion of art and technology, Traubeck has developed a record player that translates the unique colors and patterns of tree rings into hauntingly beautiful melodies. His creation bridges the gap between the natural world and the realm of music, transforming something as static as a tree trunk into an instrument that can communicate its history through sound.

The way Traubeck’s record player works is nothing short of ingenious. Unlike traditional vinyl records that rely on grooves to produce sound, this device uses light to analyze the delicate patterns of a tree’s cross-section. A PlayStation Eye camera is employed to scan the rings, capturing their details in real-time. These intricate patterns are then processed by a computer and converted into musical notes using a digital audio workstation known as Ableton Live. What emerges from this process is a uniquely composed piano piece—one that is dictated entirely by the organic structure of the tree itself.

The result is an otherworldly melody that seems to whisper secrets of the natural world. Unlike conventional music with structured harmonies and predictable chord progressions, the compositions generated from tree rings possess an ethereal quality. They evoke a sense of mystery, much like the haunting background music found in silent films or experimental ambient soundscapes. Every tree produces a melody that is entirely its own, shaped by the distinctive patterns of its rings. No two trees will ever create the same piece of music, as each tree has lived through different conditions and experiences. This uniqueness gives each song an identity, almost as if the tree is telling its personal story through music.

Traubeck’s invention has opened up a world of possibilities, sparking interest not only in the art community but also among scientists and environmentalists. It offers a new way of appreciating trees—not just as towering natural wonders but as living beings with rich histories embedded in their very structure. Imagine walking through a forest and knowing that within each trunk lies a melody waiting to be heard. Each tree, whether young or ancient, holds within it a record of time, etched in delicate lines that can now be interpreted as music.

Beyond its artistic appeal, this project carries a deeper message about nature and our relationship with it. Trees are often viewed in a practical sense—either as sources of shade, lumber, or elements of landscaping—but this project reminds us that they are so much more. Trees are living archives of the Earth’s past. They bear silent witness to history, standing tall through changing climates, environmental shifts, and human influence. By transforming tree rings into music, Traubeck encourages us to listen—truly listen—to nature in a way we never have before.

This innovative approach to sound and nature also sparks curiosity about other possible applications. Could this technology be expanded to other organic materials? What other natural structures might contain hidden harmonies? The idea that nature itself can be a composer challenges our perception of where music comes from and broadens our understanding of what can be considered an instrument.

Perhaps one of the most profound aspects of this concept is the way it invites us to see trees not just as passive parts of the landscape, but as storytellers. Each ring is a chapter, each variation in pattern a different verse. The music they produce is a reminder that life, even in its most silent forms, carries a rhythm, a beat, and a melody.

The next time you find yourself in nature—whether you are walking through a park, hiking in the mountains, or simply sitting beneath a tree in your backyard—take a moment to reflect on the hidden music that surrounds you. The wind, the leaves, the birds, and even the trees themselves are all part of an intricate symphony that plays on, whether we choose to listen or not. And thanks to artists like Bartholomäus Traubeck, we now have a way to hear one of nature’s most intimate compositions.

So, as you stand in the presence of a mighty tree, consider the symphony within its trunk. It’s a perspective that challenges us to engage with nature beyond what we see or feel. There is music in the world all around us—sometimes, we just need the right tools to hear it.