Patrick Adiarte, a talented actor and dancer best remembered for his portrayal of Ho-Jon in the first season of the hit television series MASH*, has passed away at the age of 82. His death, which was due to complications from pneumonia, was confirmed by his niece in a statement to The Hollywood Reporter. Born in Manila, Philippines, in 1943, Adiarte’s life was shaped by historical upheaval, cultural transitions, and an unwavering commitment to the performing arts. He lived through the final years of World War II before eventually immigrating to the United States, where he would go on to make a lasting impression in both film and television during a time when opportunities for Asian-American actors were severely limited.

Adiarte’s early career was defined by his appearances in iconic Hollywood musicals that have since become classics. One of his most notable roles came at a young age when he was cast in The King and I (1956), a musical by Rodgers and Hammerstein. In the film, he played the part of Prince Chulalongkorn, the Crown Prince of Siam, acting alongside Yul Brynner and Deborah Kerr. His performance demonstrated not only his natural charisma but also a refined sense of movement and expression, something that would define his work across multiple mediums. Just a few years later, he appeared in another Rodgers and Hammerstein production, Flower Drum Song (1961), which was among the first major American films to feature a predominantly Asian cast. Adiarte played Wang San, the younger brother in a Chinese-American family struggling with generational and cultural expectations in San Francisco. His work in Flower Drum Song stood out for its balance of humor, innocence, and emotional depth—a role that captured the experience of many Asian Americans during that time.

Though film brought him initial recognition, Adiarte’s television career extended his reach to American households nationwide. In addition to his role in MASH*, he had guest appearances in some of the most beloved TV shows of the 1960s and 1970s, including Hawaii Five-O, Bonanza, Kojak, and others. His presence on these shows was groundbreaking for its time, offering rare representation of Asian characters in mainstream American media. He often played roles that defied the usual stereotypes, thanks in part to his ability to bring humanity and nuance to every character he portrayed. In an industry still dominated by limited and often one-dimensional depictions of Asian people, Adiarte carved out a niche for himself that would inspire future generations of performers.

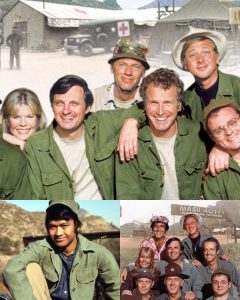

Despite these accomplishments, it was his role as Ho-Jon on MASH* that remained most memorable to audiences. The series, a satirical comedy-drama set during the Korean War, became one of the most acclaimed television programs in history. Adiarte’s character was introduced in the first season as a young Korean houseboy working for the doctors at the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital. The character was not only endearing but also significant in terms of the show’s broader themes of war, humanity, and cross-cultural relationships. In one of the season’s most heartfelt storylines, the surgeons pool their resources to help Ho-Jon get into an American university, only for him to later be conscripted into the South Korean army. This arc brought attention to the personal toll of war and the fragility of dreams in times of conflict. However, after the first season, the writers chose to phase out the character, and Adiarte did not return to the show. Still, Ho-Jon left a lasting impression and became a touchstone for early representation of Asian characters on American television.

Adiarte was not only known for his acting talents but also for his exceptional skills as a dancer. His movements were graceful yet powerful, a style that drew the admiration of some of the most respected figures in dance and choreography. None other than Gene Kelly, a legend in the world of musicals and dance, once referred to Adiarte as someone who could potentially follow in the footsteps of Fred Astaire. Such praise from Kelly was not given lightly and signified the high regard in which Adiarte’s talents were held within the industry. Yet even with this promise, Adiarte chose a path that veered away from fame in his later years. Instead of continuing to chase roles in front of the camera, he turned his focus toward sharing his love of dance through education.

In his post-Hollywood life, Adiarte dedicated himself to teaching dance to younger generations. He taught at various institutions, including Santa Monica College, where he encouraged students to find joy and discipline in movement. For Adiarte, dance was not just a performance art but a way of connecting with others and expressing identity. His students remember him not only for his technique and instruction but also for his kindness and humility. He brought the same passion to the classroom that he once brought to film sets and television studios. He helped shape the lives of countless young dancers, many of whom may not have known about his early fame but were deeply impacted by his mentorship.

Patrick Adiarte’s story is one of resilience, talent, and quiet influence. From a childhood shaped by war to becoming a face of hope and aspiration in mid-century American media, he lived a life that bridged cultures and broke barriers. In an era where Asian-American representation in entertainment was nearly invisible, he stood as a rare example of visibility and versatility. He worked with grace in an industry that was not always welcoming and left a mark that will continue to be appreciated by those who value diversity and dignity in storytelling. His passing is a reminder of the many contributions made by trailblazers whose names may not always be at the top of marquee lights but whose legacy endures in the work they inspired and the lives they touched.